On “Photography”

We need a new term.

Cameras

Let’s start with the basics… photography and cameras are not the same. Cameras have existed long before photographs.

The camera obscura, which projects light from a small hole onto a wall on the opposite side of a darkened room, has been written about as early as the 4th and 5th centuries BCE.

In his book “Secret Knowledge” (2001, link) David Hockney lays out a compelling case for how painters used camera obscura technologies as early as the early 15th century. (A side note - I’m a huge fan of this book!) He talks about how artists such as Caravaggio used pinholes, mirrors and lenses to project scenes onto canvases which they would then paint. About Caravaggio Hockney wrote:

Even his contemporaries remarked that he never drew. “He can’t paint without models” was a contemporary criticism of his work. The same, of course, could be said of any photographer.

And for hundreds of years painters continued using and developing cameras, and finding new ways to use them.

In the 1820s inventors found ways to take the images that were created by cameras and fixing them, using a chemical process, onto a surface. Originally the surfaces were glass or pewter plates, but then in 1832 Brazilian inventor Hercules Florence developed a process to affix the image to paper and named it Photographie. Soon after film was created, which also used a chemical emulsion to make its surface light sensitive. And so “photography” was born.

When digital cameras were invented in the 1980s, the photographic (ie. chemical) process involved in making images began to disappear. Digital cameras, instead of using film, capture light with electronic image sensors that then process and store that data. And while photographic printing of images continued for a while, most printing today is with high resolution inkjet printers.

In addition, unlike film cameras, which purport to preserving what they see without any modifications, digital cameras do tremendous amounts of digital manipulation to what is captured. They adjust white balance, reduce shake, improve focus, simulate depth of field and, increasingly do things to make us look better, such as skin smoothing. (This has come to be known as computational photography.)

And so, except for a small handful of prople who still use film cameras and print on photo paper, the chemical process which defines photography has passed. We continue to use cameras in order to create images, but we are no longer making photos.

AI and Photography

While the question of what a “photograph” is has hovered around since the beginning of digital era, it seems to be back again, even stronger now, with advances in artificial intelligence.

Take, for instance, Boris Eldagsen (link) and his recent win of a Sony World Photography Award. After the announcement Boris refused to accept the prize — saying that because the image was “co-created” with AI, Sony should not have allowed the entry.

This has caused controversy in the photographic community. Boris even told the awards group that the image was AI produced, and not a photograph, but they didn’t seem to care. Clearly he understand what’s going on — he even chooses to call his works PROMPTOGRAPHY rather than photography.

Eldagsen says that he calls his work “images” and not “photographs” since they are “synthetically produced, using ‘the photographic’ as a visual language.” (link)

I’d argue that, AI or not, this work is not a photograph because it did not use film or a chemical process to create a print. It is a digital work. It may look photographic, but it is something else.

If anything, Sony needs to either change the name of the award and remove the word “Photography” or else be a lot more strict about what they allow to be submitted and their methods of vetting those entries.

Post-Photography

“Photography” and “photograph” are outdated terms. Their chemical processes have been made obsolete by digital technologies. In the book “Automated Photography” (2021, link) Milo Keller writes:

I declare that photography has been replaced by photorealistic images: illusions of the world, composite digital interpretations provided by automated machines, independent of human control.”

We clearly need a new term to describe the creative activities of image making. Some have chosen to use “post-photography” — to make explicit that we have moved past the photographic era.

But that term is not without its own problems. In the essay “Post-Photography: What’s in a Name” (2021, link) Wolfgang Brükle and Marco De Mutiis write about this as they considered using it:

To some people, “post-photography” sounds like a door being shut … we went for a term which is admittedly just another result of avoidance strategy that comes with so many termino-technological post-its.

Worse still, we had already been outpaced. A series of annual conferences had … in repeated attempts to posit an “after” for a concept that was apparently only “post” in the past. Has the present of a medium ever been framed in a more historically self-conscious way?”

(Well - what about post-modernism?) But we all agree — we are in a new era and to give it a name based on its predecessor feels backwards-looking. We need a new name.

What about “darktaxa?”

How choose a new name? The artist group darktaxa project (link), of which I am a member, chose “darktaxa” as a name to hold this new type of image.

The name darktaxa is borrowed from taxonomy, where it refers to animals that exist but do not yet have a name or have not been assigned to a species.

The group’s work exists artistically and theoretically at the interface of photography and post-photography using the new digital imaging processes such as photogrammetry, augmented reality, 3D scanning, and AI. It is an acknowledgement of the way in which technology has changed image making.

The recent exhibition “Expect the Unexpected” (link) at Kunstmuseum Bonn features several darktaxa artists and gives a good survey of how the photographic world has morphed into something new. For example, this image by darktaxa artist Beate Guetschow (link), was created with a combination of photography, photogrammetry, and 3D software techniques. It may look photographic, but it is clearly not a photo.

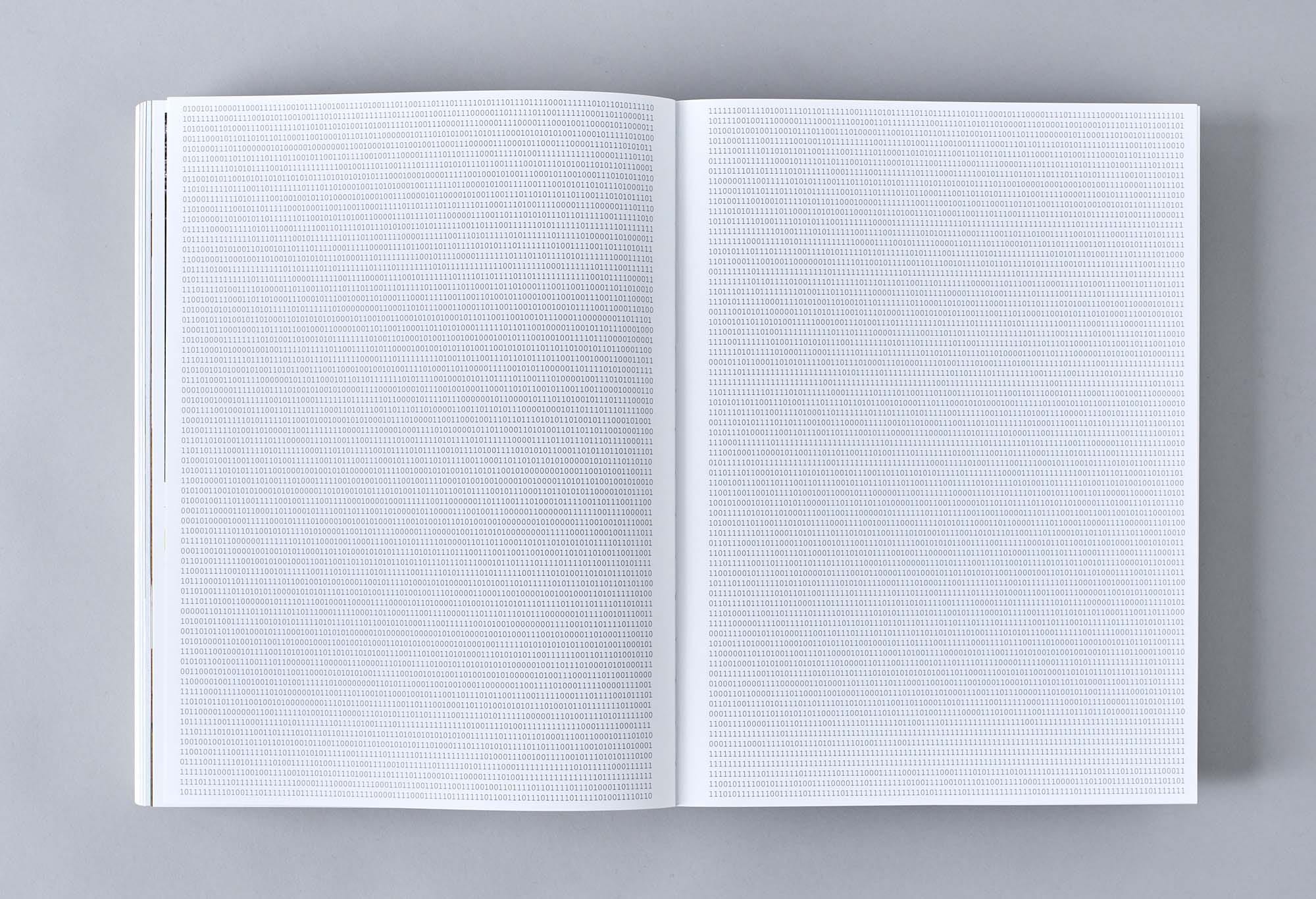

Another example is this work of mine, created in collaboration with Michael Reisch (link). “DTC-1” (“darktaxa camera 1”) is an examination of how digital images are captured, stored, and represented. It’s an attempt to strip a digital camera to its most fundamental elements, abandoning any pretense or history of film, and without any of the computational capabilities built into contemporary digital cameras.

When “DTC-1” takes a picture it doesn’t generate a jpeg file. Instead it outputs a text file containing the zeros and ones of the binary image. This text can be displayed on the camera’s screen — which takes 14 days to scroll through — or printed — requiring approximately 53,000 pages.

I don’t think that anyone would confuse 53,000 pages of zeros and ones with a photograph. But it is an image.

The future is already here

A painting is a painting because it is made with paint. A photo is a photo because it is created with a chemical process. And both painting and photography have used technology, such as cameras, to aid their creation. Today cameras are being used to create something new. We just haven’t yet agreed on a term for it.

Will “darktaxa” become the new term to replace photography? Probably not. I’ve never heard anyone outside our group refer to their work as a “darktaxa.” But let’s acknowledge that most of us are no longer making photographs.

Photography is undead, a zombie, it is expanded in a way, that we cannot speak of photography any more. But still we use the term all the time. We need to fill this whole field with new meaning and find new terminology.

— Michael Reisch

What’s wonderful is that, as we move away from old terms, we can see more clearly that this new thing has actually been around for quite a while — and it has a beautifully rich history. The earliest photographers were already pushing the boundaries of their medium with cameraless photography (see this article from the V&A museum). And digital art has been around and vibrantly active since the days of the earliest computers (the exhibition “Coded” (link) at LACMA highlights work back to the 1950s). We’re now able to see more clearly how these threads have been leading to today’s creativity.

This isn’t to say that people shouldn’t still be making paintings or photographs. But there’s something else happening, too.

As an artist I find this new space especially exciting. There is amazing work being made. Fascinating conversations are being had among artists, curators, collectors, and even institutions. And every day there are creations and ideas that are unlike anything we’ve seen or heard before.

We have moved out of that [photographic] period, and the consequences are unknown.

— David Hockney