Turtles All the Way Down

AI systems are hiding things from us, but maybe there are ways to see what's going on.

There was a quote in a recent New York Times piece "The Surprising Thing A.I. Engineers Will Tell You if You Let Them" (link) that really caught my attention:

"…every expert I talk to says basically the same thing: We have made no progress on interpretability" (getting AI systems to explain their output) ... "For now, we have no idea what is happening inside these prediction systems. Force them to provide an explanation, and the one they give is itself a prediction of what we want to hear — it’s turtles all the way down."

“Turtles all the way down” is a mythological idea that the world rests on the back of a turtle which, in turn is on the back of a larger turtle, and so on… a stack of turtles that goes on indefinitely. When applied to AI, this metaphor means that all levels, or scales of AI are unknowable.

I first wrote about the unknowability of AI in my 2019 essay Tabula Rasa. Back then I was thinking about the organic nature of knowledge contained in AI neural networks, and the impossibility for us to interrogate and understand them. Has anything actually changed since then?

With the recent rapid advances in AI, 2019 can seem like a lifetime ago. New systems have capabilities that we would have never imagined. This is, in part, because they are trained on so much more data. For instance, ChatGPT-4 was trained on 570 GB of data. Dall-E 2 was trained on 650 million image pairs. These are quantities of data so vast that we can’t really comprehend them. And the outputs of these systems, although flawed, often appear “correct” or “perfect.” But that seeming fidelity makes it even harder for us to imagine what’s happening behind the scenes.

I approached my Tabula Rasa work with the belief that reducing the amount of data that the machine was trained on would reveal something about how it worked. In the universe of stacked turtles, I wanted to look at turtles lower than those being used commercially. And so I used tiny training sets — some as small as one or two images, solid colors — aiming to break the machine. The results revealed a kind of “materiality” to AI… a mix of organic and digital qualities. And occasional surprises, too, such as when, trained on just two colors, the machine would “invent” other colors.

Lately I’ve been revisiting this project because that the flaws that were inherent in earlier machine learning are still present in today’s systems. I’m heartened to see increasing awareness and concern about this in so many conversations. And I believe that art is an important part of the conversation. Art allows aesthetic experiences, rather than technical explanations, to engage people to think about what AI is and might be.

To this end I’ve been applying new methods to both train the machine on limited data, as well as to examine and further manipulate its output.

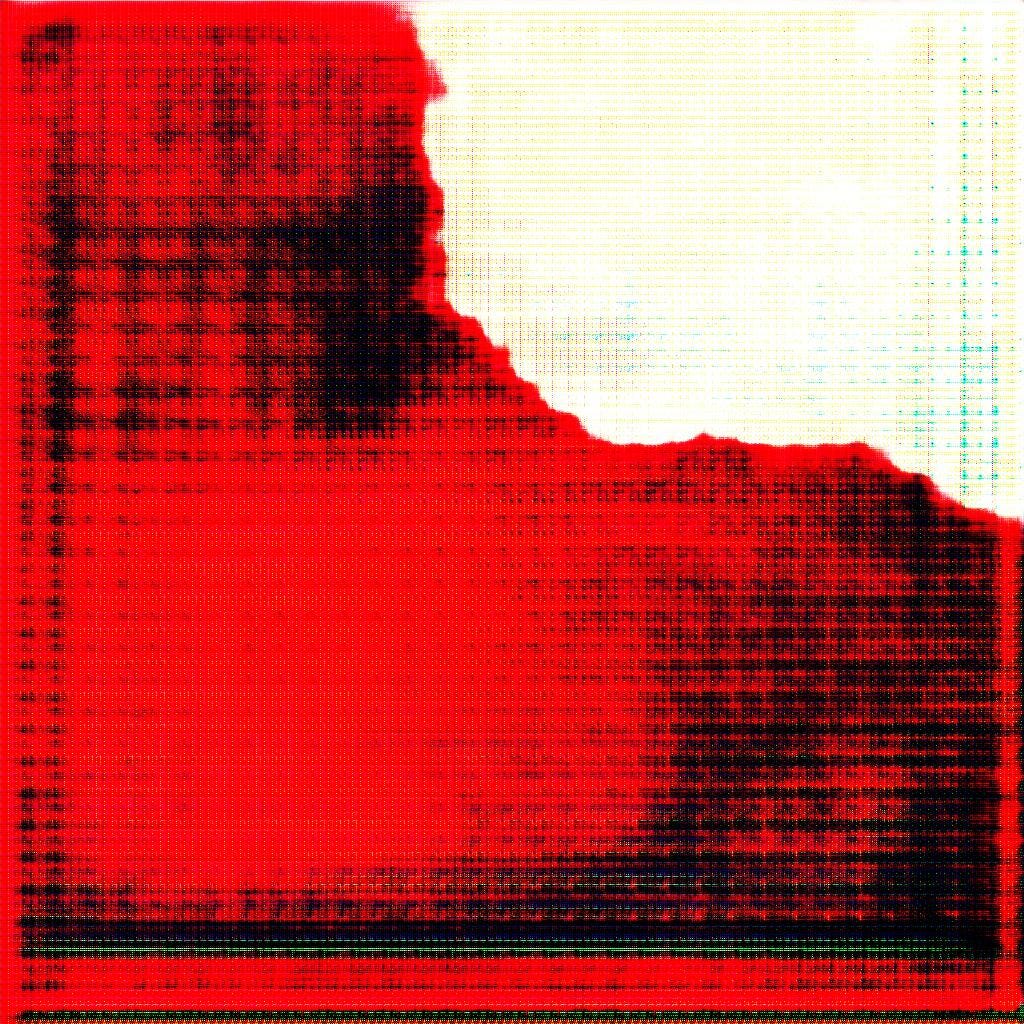

Here’s an example… the machine generated this image after being trained on just two solid colors:

At first it may not appear to be very interesting, but the strange materiality of AI is revealed in its mix of digital and organic qualities — the grid that reveals itself in the darker areas and then the blobby light and dark shapes that compose the image. There is uncertainty between foreground and background.

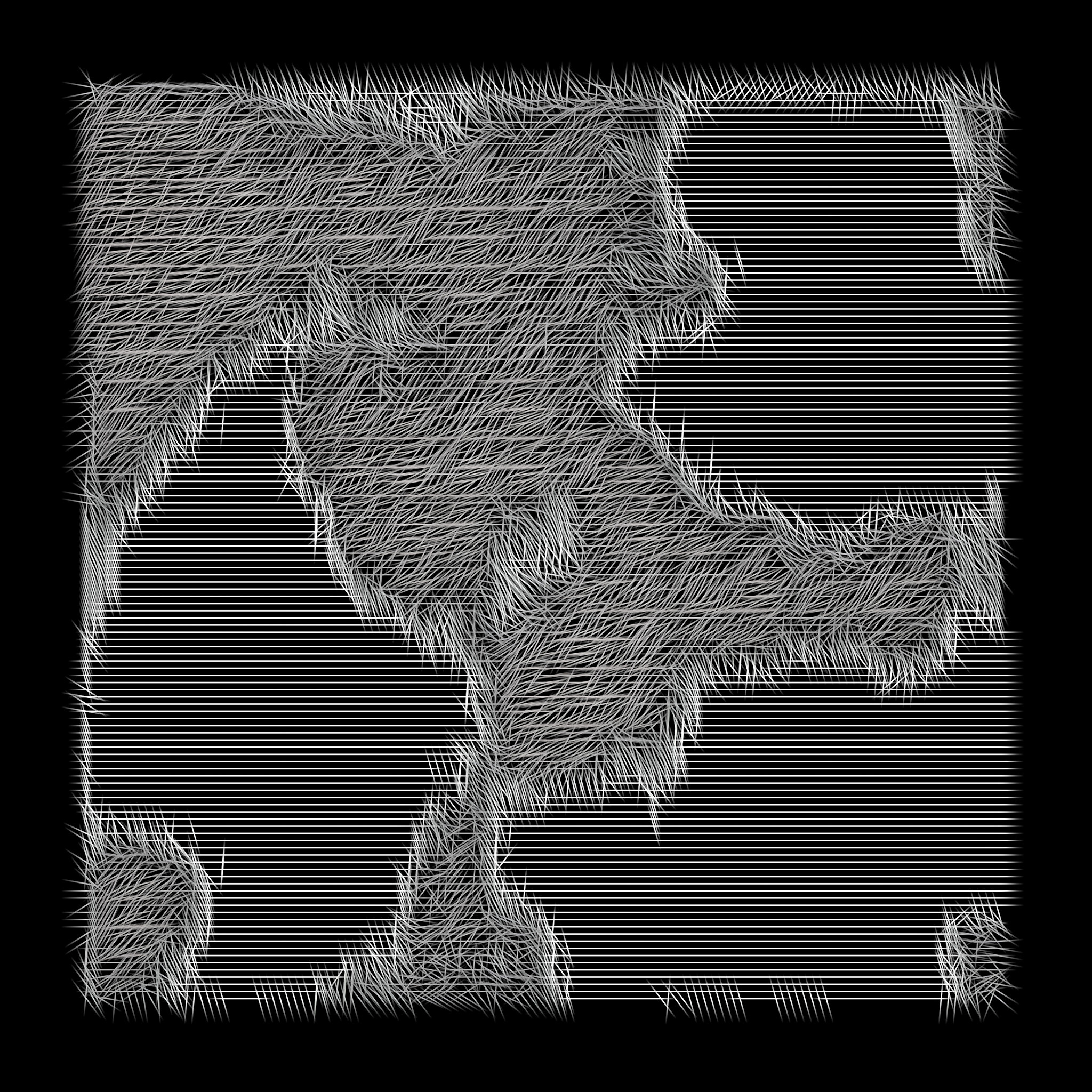

But there is more to this image than meets our human eyes. With some “manipulation,” using software I developed, we get a very different version:

What we might have seen in the first image as a tension between white and black, instead looks like the white areas (where there are horizontal likes) were ignored by the machine. It’s the dark areas where the activity lays. And at the boundaries of what was white and black — the front of the black boundary’s movement — we see a different energy. Perhaps an energy of transition, vs the grey’s energy of trying to settle to a solid state.

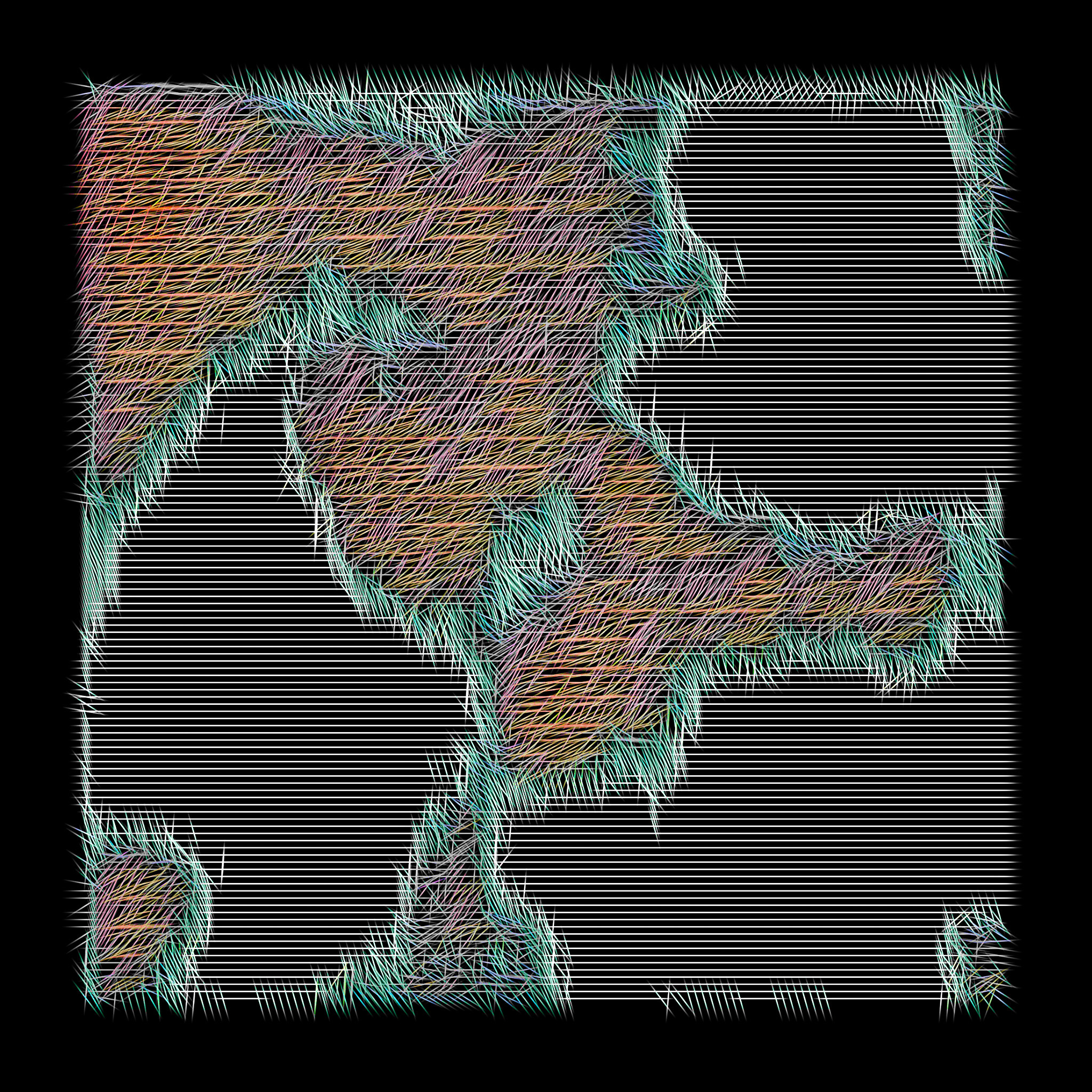

But this image is still hiding something from our human eyes. With further manipulation we get:

Color! This color might be obvious to the machine — there is clearly a logic to how color is being used — but it doesn’t make it obvious, or even apparent, to us. In the boundary between white and black emerges green. And in the grey areas, textures of purple, orange and yellow.

If we take this example of low fidelity back up the stack of turtles, to today’s language model systems, it begs the question: is it possible that within the text output of ChatGPT there are embedded and hidden the verbal equivalents of visual color? And if so, how would we know that they are there? And what would they reveal?

For now we don’t have the technology to answer to these questions. But art can give us a head start. It can make visible the strange non-humanness of AI. It can question the assumption of AI’s inevitability and perfection. It can help us approach AI with confidence. And maybe it can even lead to alternative ways of using the technology.